Why Do It?

If you’re aiming for a licensing agreement with a company, this is the last lap. You’ve got a company interested and you want to negotiate a deal that nets you the best royalty rate possible. But even though things are looking good, there’s still a lot of scope for making mistakes that can leave you with no deal, or a much poorer one than you deserve. This Project runs you through the whole process of doing business with a half-interested, then a very interested, company. With luck, you may emerge from it with a licensing agreement good enough to make your marathon of pain and frustration seem highly worthwhile.

Initial Assessment By Companies

What companies look for in a new product idea

Understanding how companies have to look at new ideas is an important part of the battle to win them over. Their ideal is an idea that will give them a mountainous profit for no risk. They know they’re unlikely to get it, but that’s the direction they’ll be coming from. Not in a month of Sundays will they look at your idea and say: ‘Hey, this is so good we must do it, no matter what it costs us!’ Before taking any risk involving a hefty commitment of funds or time, a company must be satisfied that everything about your idea stacks up.

Key factors they’ll look at include:

- The product: Does it fit in with their marketing strategy and longer-term business plans? What impact will it have on their other products? How much more development will it need? (Probably far more than you think.) Can it be manufactured cost effectively?

- The market: What’s the sales potential? What’s the right price? Is the market ready? What’s the best market entry strategy? How much may have to be spent on marketing and promotion? How are competitors likely to react? How are distributors, retailers and perhaps even their own sales people likely to react? What will be the consequences if they don’t run with the product but a competitor does?

- The IPR: How extensive and valuable is it? Is it dependent on the inventor’s know-how? If so, will that know-how be available? Regardless of IP status, is the idea novel now, let alone after a possibly lengthy period of development? Is the IP strong enough to resist competitors’ attempts to circumvent or challenge it? Who will own, pay for, protect and enforce the IPR?

- The cost: Is the project affordable and how would it be financed?

- Risk versus return: Would the project pose a significant risk to the business? How soon will the product recoup costs and go into profit? How long is the profit likely to be sustained? If the product takes the company into unfamiliar territory, how are shareholders likely to react? (In some larger companies, keeping twitchy shareholders happy is virtually the only thing senior executives care about.)

- The inventor: Is the inventor an asset or a liability? Does he or she behave professionally enough to enable both sides to make reasonable progress towards a licensing agreement? If not, is the product outstanding enough to make the pain worthwhile?

If this list seems to duplicate tasks covered in other Projects, don’t think that because the company will do them, there’s no need for you to do them. First, you’ll look like a complete time-waster if you appear to have done nothing to make a case for your own idea. Second, if they find evidence that in their view demolishes your idea, you’d better have enough evidence of your own to argue that they’re wrong.

You also need to bear these points in mind when you strike up an initial relationship with a company interested in at least assessing your idea:

- Companies have very limited freedom to act on impulse. They must carry out a full cost and risk analysis (the due diligence process mentioned in Project 8) before committing themselves to any significant new idea.

- Post-assessment rejection doesn’t necessarily mean a company thinks your idea won’t succeed. It means they think it isn’t right for them. It’s difficult for this kind of decision to be reached entirely objectively, so the more positive evidence you can present or (particularly when it’s a small company) the more input you can offer to make a development project succeed, the more you may be able to influence the verdict.

- Don’t sit back and expect the company to do everything right. Companies are not infallible and a small firm may be no more experienced at innovation than you. Plenty of companies launch products that flop, so your own input may be essential not just to further your own interests but to help the company as well.

- For best results even with large companies, be prepared to offer or accept some kind of joint venture (see Project 6). It shows a can-do attitude and will win you more points than if you simply sit there and expect the company to make all the effort.

Keeping Control Of Your Prototype

See also Project 4, as much of it will be relevant here too.

If you have a prototype, expect an interested company to want to keep it for a period of detailed assessment. This is where you can come unstuck, especially if you only have one prototype. You don’t want it locked inside one company for months on end, especially if you’ve filed a patent application.

It’s difficult to meet both your own and a company’s needs with a single prototype, but the following guidelines may help you to stay in control of what is after all your property.

- Don’t leave a prototype behind at first visit. Tell the company you’ll let them assess it subject to a formal written agreement on conditions of loan, drafted or okayed by your solicitor or patent attorney and signed by the company. It needn’t be long or complex but it should cover clearly and unambiguously most of the issues listed below. If the company won’t co-operate, write them off. If they can’t respect you even at this basic level, it’s probably too risky dealing with them at all.

- Establish what they physically want to do with your prototype, and who will be responsible for its safe keeping. Will they pay for immediate repair or replacement in the event of loss or avoidable damage? (If they won’t, try charging a deposit that will cover repair or replacement. Explain clearly that you’re only doing it as a form of insurance.)

- Negotiate firmly for the shortest reasonable loan period and insist on a specific end date, which is written into the agreement. If their interest seems lukewarm and there’s a risk your prototype might end up on a low priority slush pile, don’t release it for more than 15 working days. They can always negotiate a second loan later.

- A month ought to be ample for most initial assessments. Don’t loan your prototype for significantly longer without some form of payment. This is important. Without that spur a company may hang on to it indefinitely and most likely forget about it.

- The more the company wants things its own way - for example lengthy and exclusive assessment rights, barring you from even talking to other companies - then (1) the more they must pay for their privileges and (2) the more vital it is to have a legal agreement on conditions of loan.

- Most companies won’t want to pay, so if you feel out of your depth let a patent attorney or someone else suitably qualified negotiate a loan period for you, especially if it’s a high- stakes product. But: don’t lose sight of the fact that a rapid yes or no decision is equally important, so bid for a speedy outcome as well as cash.

- How much the company should pay depends on the potential value of the IP. It should be enough both to compensate you for not approaching their competitors and to stir them into brisk action. If the terms offered are derisory, walk away. A possible exception is if there are potential deferred benefits - for example if it’s a small company with a keen interest but no spare cash, or if the company guarantees to research the market or make samples which belong to you if they drop out.

- Payment in instalments is more acceptable to companies than a lump sum, so ask for £X a month or part month for any period beyond (say) 30 days. Agree a termination date and make it clear in your contract that on that date all their rights lapse. Also insist that if an instalment fails to materialise when due, the deal is immediately void.

- Insist on payment by standing order. It’s no hardship for the company and it's then less easy for someone in the company to mess you around by ‘forgetting’ an instalment.

- Payment should also cover or contribute towards patenting or other IPR costs during the loan period. There are two options. The more likely is that you pay for patenting and build as much of the cost as you can into your loan period payment. Less likely, because it signifies an almost immediate commitment to your product, is that the company pays directly. They might want co-ownership of the IP, but this could be a price worth paying if it relieves you of a potentially very large financial burden. Guidance from a patent attorney will however be essential, and you must insist on continuous proof that the company is doing everything correctly and on time; the patent process keeps strict deadlines and any delay or omission can be fatal.

The Art and Craftiness of Negotiation

Calculating Royalty Rates

Where does your royalty come from?

A few basic facts of life first:

- Your royalty percentage will always be a share of the price the company gets when it sells product made using your IP.

- Your royalty income will depend entirely on sales. A company could quite conceivably acquire a licence from you but for a variety of reasons not make or sell any product. You then wouldn’t get any royalty payments at all unless your licensing agreement included a guaranteed minimum income (see later).

- If your product is sold on down the supply chain, its price will rise but neither you nor the company will normally get any share of its increased value. You therefore can’t easily base your royalty percentage on the retail or ‘shop’ price of your product.

Most royalties experts agree that the maximum royalty you’re likely to get is about 25 per cent of the gross profit the company expects to make from your product. So your first task is to work out what that gross profit is likely to be.

Gross profit is the company’s ‘factory gate’ price per unit minus the cost of production and selling, and will depend on the number of units sold per year. The maths is simple as long as you have two pieces of information:

- The company’s sales forecast for your product.

- The company’s proposed selling price.

If you don’t already know the manufacturing cost of your product, there are two ways you can get reasonably close to it:

- By using the standard industry 80:20 assumption, which is that 20 per cent of the components – the most expensive ones - will account for around 80 per cent of the total product cost.

- By asking other companies to quote for a similar product (same basic technology, materials, dimensions etc) based on the quantities in the sales forecast. It has to be said though that in practice, getting such quotations isn’t likely to be easy.

Knowing that 25 per cent of gross profit is your probable maximum doesn’t on its own get you very far. Most companies won’t want to give you 25 per cent of gross profit, or anything like it. They’ll want to give you the most miserably small percentage they can get away with. Nothing, if at all possible. You therefore need to be able to convince them that you deserve more than they want to offer.

The battleground will be the value of your product. You need to decide how commercially valuable you think your product is, and bid for a royalty percentage that reflects that value. The company will go through the same process and almost inevitably arrive at a much lower valuation. You then argue and haggle until both sides either accept a compromise value or agree to part company. At bottom it’s not that much different from selling a house or car, except that it usually takes much longer and you end up not with an agreed price but an agreed percentage.

So how do you work out a value for your product? You start by understanding that it’s not (yet) a number that you’re after, but a ranking somewhere on a scale from very high to very low value. From then on, there are two rough and ready ways of assessing value: A reality check or a gross profit per unit and market size.

Reality Check

Many inventors overvalue their products (or more accurately, don’t attempt to value them at all) and ask for an unrealistically high royalty. This can get negotiations off to a bad start from which they may not fully recover. A reality check like this can help you to bid more credibly, and thus more successfully. It may even make you realise you’ve undervalued your product. Simply adjust your royalty expectation up or down as you answer these questions. It’s all very approximate but it may help you to gauge whether the percentage the company offers is derisory or merely at the low end of realistic.

- What’s your contribution to the product? If all you’ve really done is give the company an idea that they’ve turned into a product through their own efforts, and especially if they’re paying upkeep costs such as patenting, rate your royalty prospects as poor. But if you’ve done the lion’s share of development and given the company a near- perfected product, you deserve a larger than average percentage.

- How special is the product? If it’s a 'so- what?' product (Project 3) that has to be keenly priced to win any kind of market share, the company’s profit margin will be low and so will your royalty. But if there’s so little close competition that the company can charge whatever the market will bear, the higher profit margin should justify an above- average royalty percentage.

- In what quantity will the product sell? The more units sold, the lower will be your royalty percentage. Profit margins shrink as customers place larger orders but insist on lower prices, while the company may have to invest in extra production resources to meet those orders. Why should they keep paying you a fixed royalty while their profit goes down? The perfectly correct business view is that even at a lower percentage your income will multiply if sales go through the roof.

Gross Profit per unit and Market Size

A good indicator of value is an estimate of the product’s gross profit per unit and probable market size. You’ve already got a figure for gross profit per unit, so all you need to know is the size of the probable annual market for your product. The company’s sales forecast should tell you this but it may be overly conservative, partly out of sensible caution and partly to stop you getting ideas above your station. If you have reason to doubt the company’s forecast, do your own research into market size.

The bigger the potential gross profit per unit, the higher the value of the product. For example: Mousetrap X can be made for a penny and sold for a pound, while Mousetrap Y costs 50 pence to make but can’t sell for more than a pound. By this measure, Mousetrap X is far more profitable and thus more valuable and thus more deserving of a better-than- average share of gross profit as a royalty.

But that’s only half the picture. We need to take market size into account as well. For example, a product that promises to sell in huge numbers for several years has a higher value than a product with the same gross profit per unit but only a limited life in a small market. If our Mousetrap X has years of high- volume sales ahead of it, it’s a clear overall winner in the value stakes. But if the market for mousetraps is shrinking fast as fewer homes have problems with mice, its value will be diminished despite the healthy gross profit. And if Mousetrap X is a flimsy, throwaway product while Mousetrap Y is robust and reusable, Mousetrap Y might in the long term be a better seller.

Overall value therefore depends on averaging out several value-related factors. Depending on circumstances, exactly the same mousetrap could easily have anything from a very high to a very low value for royalty purposes. For example:

If you want to combine your reality check, gross profit per unit and market size values it might help to draw up a scale from 1 (very low value) to 10 (very high value). Give your product a score out of 10 for each factor:

- Your contribution to the product.

- How special is it?

- Sales quantities.

- Gross profit per unit.

- Market size.

Converting Gross Profit Into Net Sales Price

We hope you’ve understood everything so far, because here’s where we have to make a switch from gross profit to net sales price.

Up to now we’ve talked only about gross profit because that’s the most accurate measure of your royalty expectation. However, it’s standard business practice to negotiate and express royalties as a percentage of the product’s net sales price - that is, the ‘factory gate’ price minus all taxes. Net sales price is a better yardstick for businesses than gross profit because it reflects the difficulty of making an actual profit.

Shifting from gross profit to net sales price is no worse than converting from imperial to metric measures: the terminology changes but the thing you’re measuring doesn’t. Or you can look at the difference like this:

- Before negotiations you think percentages of gross profit, because it’s more accurate.

- During negotiations you talk percentages of net sales price, because that’s simpler and it’s the language of business.

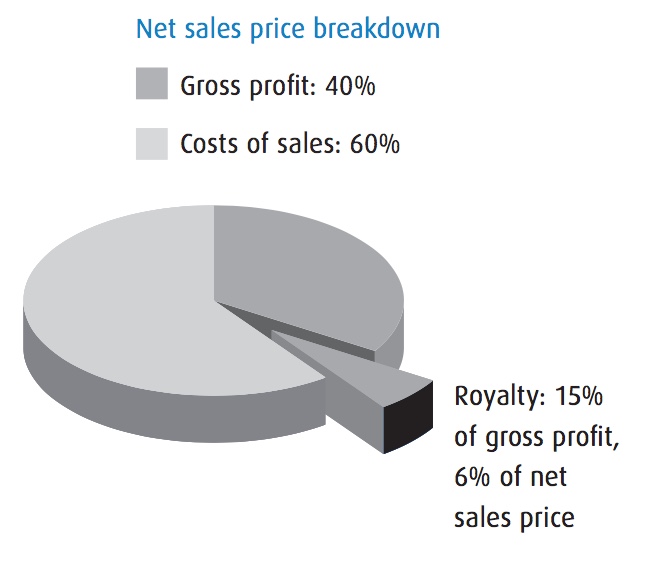

The pie chart shows that:

- The company stands to make 40% gross profit on a year’s sales of your product.

- You’ve decided that you can justify 15% of that gross profit.

- That now becomes 15% of 40%…

- ...which works out at 6% of net sales price.

Typical Royalty Percentages & Renegotiation

Most royalties probably fall into the 2-7 per cent range of net sales price. The lower end is for products which sell in large quantities (typically hundreds of thousands), while the upper end is for products which sell at more modest levels (typically tens of thousands). A royalty of 4-7 per cent of net sales price for an ‘average’ product is good going, while some specialised products such as industrial software or medical equipment should exceed 10 per cent without too much trouble. Don’t however be outraged if offered a fraction of one per cent for a product likely to sell in endless millions. Do the sums and rejoice.

Don’t expect your royalty percentage to be forever. A typical product life cycle consists of three phases: modest but rising early sales, good peak-period sales, then falling sales as competitors catch up or the technology becomes obsolete. Whenever sales and profit change significantly, expect the company to want to renegotiate your royalty. This is quite reasonable, so a worthwhile negotiating tactic is to accept or even suggest a sliding scale of royalties based on the total royalty income involved. For example: seven per cent up to £20,000 per year of total royalty income, reducing to five per cent between £20-50,000 and to three per cent when your total royalty income exceeds £50,000 per year. This shows that you acknowledge the company’s falling profit margin as sales rise, and demonstrates your professionalism and willingness to be flexible in everyone’s best interests.

Don’t however let yourself be too easily persuaded to accept a lower royalty. In some situations gross profit may actually rise as sales decline. Production equipment may be fully paid for and thus cost next to nothing to run, and components may become cheaper by the same process or as market demand for them drops. To avoid becoming an easy touch, keep yourself fully up to date about the state of the company, its suppliers and purchasers, and that market or industry generally.

- Never accept a royalty agreement that stops paying out once a specified level of sales is reached. Your royalty should apply to all sales, whether or not they exceed the company’s sales forecast. The only possible exception is if you’re offered the option of accepting a royalty cut-off for a substantial guaranteed minimum royalty income.

- Never agree to royalties based solely on net profit. Sales figures can easily be manipulated (that is, fiddled) to show no profit at all, and with a little ingenuity almost anything can be deducted from profit as a business cost. Even tax inspectors have a hard time here, so you won’t stand a chance of disputing the company’s figures.

- Always make sure the company gives you a royalty based on a fair market price. A favourite trick of some companies is to sell product at an artificially low price to one of their own subsidiaries or to an associate company. This deprives you of royalties but can be hard to detect, so to reduce the risk insist in your final agreement on royalties based on arm’s length transactions. This means that if the company tries to pull a fast one, a court can uphold your right to a royalty based on a higher price.

Negotiating Heads of Agreement

This is where you and the company sit down and thrash out the basics of an agreement, trying to find as much common ground as possible. The aim is to:

- Identify the figures, terms and conditions that both of you are broadly happy with.

- Write them up in a preliminary document called heads of agreement.

- Then hand that over to legal professionals to be rewritten as a full agreement (see later) in dense legalese.

With some exceptions - see Professional help - heads of agreement talks usually work best without formalities or legal representation on either side. It’s therefore perfectly acceptable to conduct your own negotiations as long as something positive is emerging. (It’s up to you whether to negotiate alone or with one or more members of your team. There’s safety in numbers, but too many cooks can spoil the broth. Take your pick.)

If the company adopts a ‘take it or leave it’ stance that allows no room for movement, it may be bullying arrogance or it may be their genuine view, based on experience, that this is as good as it can get for both of you. You can’t be expected to know which it is, so you should immediately seek the professional advice of a patent attorney or solicitor, not least on whether an agreement is worth reaching at all.

For your part, be prepared. You must enter negotiations knowing broadly what kind of a deal you want, and be capable of disclosing it and justifying it as talks unfold. The time- dishonoured, reactive practice of simply saying ‘not enough’ to every offer the company makes is unlikely to get you anything better than ‘Goodbye’.

The Scope of Negotiations

The following list gives you some idea of the component clauses that need to be talked through, then written up as a heads of agreement document. Its range is typical but by no means complete. Ask a patent attorney or solicitor to advise you on additional aspects specific to your idea which may need to be brought into the talks.

Heads of Agreement (Subject to Formal Contract)

3.1 What is being licensed: Give a descriptive title of your invention/ product and list all the IPR on offer - patents, trade marks, registered designs, copyrights, know-how etc - including any official numbers.

3.2 What the licensee intends: Namely, that the company wishes to exploit the invention in a particular territory and has requested that the licensor grant a licence to manufacture and sell the product(s) with the use of defined IP.

- Exclusive: only the licensee and not the licensor can manufacture the product. This may be insisted on if the product involves significant expense, lead-time or market promotion.

- Sole: only the licensee and licensor can manufacture.

- Non-exclusive: allows several licences and is typically best for add-ons in competitive industries (for example the Dolby noise reduction system).

- Semi-exclusive: licence limited by territory, type of industry, application or time.

- Assignment: a special case where the licensee completely takes over the patents and other IPR.

4.3 The market: May be defined/limited by type of industry or application. You may be able to grant several licences for different markets, thus increasing total market penetration and royalty levels.

5.2 Some guarantee of payment: To prevent the company acquiring a licence, then being either slow to work it or doing nothing at all with it. You may have to agree to any overpayment in the early, poor years being clawed back in later, better years.

5.3 Advance lump-sum payment: For most companies, making any kind of payment that doesn’t come out of product sales income is a no-no, but there are exceptions. See Doing your lump sums.

8.1 Who owns improvements? The company may develop ‘your’ technology over time, or apply it to different products. Which of you then owns the improvements? The company may justifiably object to paying you a royalty for their improvements. To cover this, try to extend the licence to include improvements, or at the very least insist that your royalty doesn’t drop if the licensee improves the product.

8.2 What if your IPR is successfully challenged? It may pay you to specify what portion of the royalty is associated with which elements of IPR: for example 50 per cent to patents, 25 per cent to trade marks and 25 per cent to know-how. That way, even if you lose all patent cover you’ll still get something. Or you might specify lower levels of payment or duration in the event of diminished IP protection.

8.3 Who challenges infringers, and at whose risk? It’s dangerous to accept responsibility for this unless you’re rich. Far better to accept a lower royalty in return for off-loading the risk. Even if you have IP insurance, don’t assume it’ll cover your litigation costs. That may only happen if the insurer expects you to win, and legal outcomes are rarely so predictable.

8.4 Manipulation of value of sales. You need to limit the company’s ability to fiddle the sales value downwards to reduce your royalty payment. The company will not unreasonably want to deduct all allowable costs, but these can be legion and at the shady end can include ‘sweetheart deals’ in which product is sold at an unrealistically low price to accomplice companies. To avoid this, specify which costs are deductible and also specify arm’s length transactions (see Nasty traps to avoid earlier).

Always Ask ‘What if?’ Questions

Expect all these clauses to be present in some form or other in your agreement, and make sure that anything else you can think of is covered too. Don’t expect the company to bat for anyone except itself, so try to work out the exact effect each and every clause will have on you. Do this by constantly asking ‘what if?’ questions, both at the negotiating table and elsewhere. Ignore any pressure to hurry up or accept clauses on the nod, and don’t be afraid to call a halt for hours, days or even weeks if you need time to think or consult someone. If any answer is unsatisfactory or you don’t understand it, insist on renegotiation until that point is clear and acceptable. Bear in mind though that ‘acceptable’ won’t always mean ‘in your favour’. Don’t forget what we said earlier about the purpose of negotiation being not to win but to reach agreement.

It may help to have your own heads of agreement drafted out in full before the meeting. Don’t disclose it, as you stand to lose too much face if the company rejects it clause by clause, as they will certainly try to do. Its better use is as a checklist to help you gauge how on- or off-track you are if the going starts to get confusing.

Doing Your Lump Sums

Let’s grapple for a moment with the issue of advance payments. Many inventors think they have a God-given right to a large up-front sweetener, but back on planet Earth the situation is more complex. Virtually no company will readily agree to an advance payment so a lot depends on how big an issue you want to make of it. If you push it too hard it could be a deal breaker, but in some circumstances the risk may be worth taking.

From the company’s point of view it’s one thing to discuss a fair sharing of future profits, quite another to hand out a hefty pre-sales sum when the inevitable accountant’s question: ‘What exactly is this money buying?’ may be very difficult to answer. A small company may genuinely be unable to afford it, especially if they’re already going to be stretched to finance your product. Therefore, one argument is that in the interests of conflict-free negotiations you should forget about a lump sum and focus on maximising your royalty percentage. That way, whatever money you eventually get comes technically from the product, not the company. The risk is that the product doesn’t sell, but that’s the company’s risk too.

A counter argument is that the company needs to show genuine commitment to selling the product rather than just acquiring a licence, and a fair way to do that is to pay you a golden hello. There may be force in this argument if:

- The IP is of high and long-term value to a major company, and you could easily go elsewhere.

- You’ll have on-going costs after you’ve granted the licence (for example, for patent renewal or developing improvements to the product) that will benefit the company and need funding long before any royalties come in.

- You have know-how or other vital documentation to be disclosed or handed over only on signing the full agreement.

Ask for your guaranteed income to be a small proportion - 25-30 per cent - of your agreed royalty on projected annual sales. Let’s say you’ve agreed a royalty of 2 per cent on projected annual sales of 500,000 units at £4 net sales price. That means your royalty income should be £40,000. Twenty-five per cent of that - £10,000 or about £830 a month - is the sort of pre-production income you can justifiably ask for. If sales remain as forecast for some years, your royalties will soon recoup even several years of advance income.

To some extent you’re challenging the company to put its money where its mouth is and that may make them uneasy. If they respond by suddenly producing ‘revised’ sales projections 75 per cent lower than before - which is in effect what they’re doing if they say your request is unjustifiable - then maybe they shouldn’t be in business.

If you want to press for an advance payment from a company that can easily afford it, good luck to you. But unless you’re either a skilled negotiator or in an extremely strong bargaining position, it won’t be easy and you could end up doing yourself more harm than good.

Finally, a company may offer a fixed sum instead of royalties if they think that in the long term the idea will make them a fortune. Smell a faint rat if such an offer comes your way, as it could be a ploy to buy you out for peanuts. On the other hand it could backfire on the company. An inventor known to us was offered the choice of £1 million for a total buy- out, or a guaranteed minimum royalty of £60,000 a year. He chose the latter, estimating a £200,000-plus annual royalty over many years. In the event, sales never reached even the minimum royalty level and after only a couple of years the product was withdrawn.

Moral: if the bribe is big enough, at least consider it seriously.

Full Agreement

If and when you’re happy with the heads of agreement, the next and final stage is to convert them into a full legal agreement.

This will inevitably be a complex and near- incomprehensible document, often scores of pages long, which neither you nor the company’s negotiators will be competent to draft. This is a job for legal specialists, though they’ll consult you on points of detail. The company will use its own advisers, so you must use your own patent attorney and/or solicitor to make sure that the final document is consistent with the heads of agreement and doesn’t conceal some elephant trap dug by the company since drawing up the heads.

For your part, don’t look on the full agreement as an opportunity to undo the deal. Best policy is simply to say to your solicitor: ‘Here’s the outline agreement. I’m happy with its terms and figures, so please draft a full agreement based on it’. Unless your solicitor or patent attorney finds evidence that something is badly wrong or unworkable, or spots a way of improving the deal for everyone, resist any temptation to try to alter what’s been agreed. Maybe you were steam- rollered here and there, but the deed must now be considered done and any attempt to wind the clock back is more likely to wreck the deal than improve it. In any case, most professionals charge by the hour, so any intervention that takes time to sort out may cost you a lot of money for not much gain and lose you valuable goodwill.

Project 10 Checklist

The following checklist is partly an action planner and partly a reminder of what matters. If you’re tempted to think ‘I don’t need to do all this stuff’, it may help to point out that we’ve modeled the checklist on questions professionals are very likely to ask if you want their advice, support or money. We therefore have to be stern and say that if you aim to be a respected and successful inventor, you can’t afford to duck any of it.

- Find out how your prototype will be tested, by whom and for how long.

- Decide what terms and conditions (including payment if relevant) to impose on any period of assessment.

- Draft a suitable ‘loan of prototype’ contract and have it checked by your patent attorney or other legal adviser.

- With input from your team, prepare/ rehearse your heads of agreement negotiating position.

- Consider who else you want to involve in negotiations.

- Be constantly aware of the need to reduce or deal effectively with conflict.

- Calculate a realistic royalty to ask for.

- As negotiations progress, ask ‘what if?’ questions to test the value and safety of what you’re being offered.

- Ensure that by the time you get to full agreement stage, you’re happy with the deal and don’t want to change anything.